Corona Glass

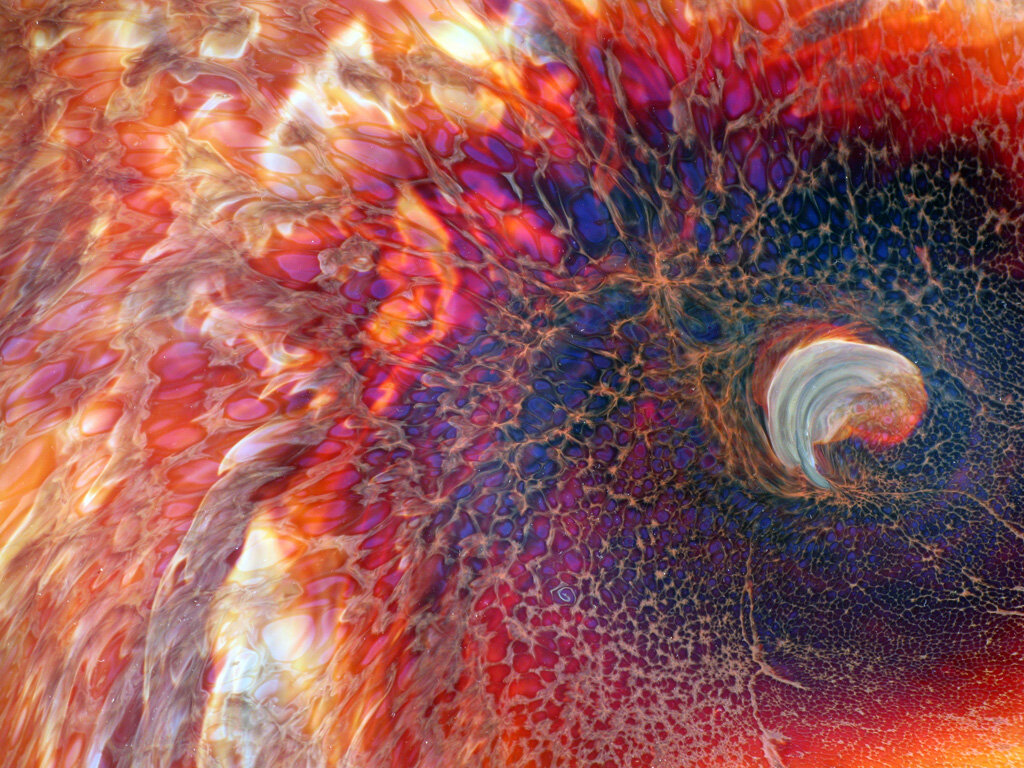

Corona Glass is the most fascinating and unpredictable material I have ever worked with. I’ve been trying to understand this glass for more than thirty years, but I still don’t know for sure how any given piece will turn out. When everything goes well, the final appearance can be just gorgeous, like a splash of liquid fire, an eddy of swirling melted light or an exploding galaxy. When things go badly, the result can be downright awful.

Some people speculate that I was inspired to invent this glass after seeing photos of nebulae, planets, stars and distant galaxies taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. However, while my Corona Glass does sometimes resemble those spectacular images, the truth about its creation is a bit more complex. It is (like my own life) a story of blind luck, stupid persistence, partially managed chaos, incremental discovery and intermittent, occasionally astonishing, success.

“Josh Simpson, who became fascinated with glass in the initial stages of the studio glass movement, has been perfecting his technique for many years. He is an artist with a solid place in the history of contemporary class. But he is also a scientist – specifically a glass chemist – who has spent decades researching ancient glass formulas and mixing chemicals to create his popular planets. With his platters, he has perfected his own version of Chalcedony glass, which he calls Corona.”

— Amy Schwartz

Director of the Studio, Corning Museum of Glass

How Corona Glass Came to Exist

It all started with an amazing accident. Back in the 1970s, as I began to learn about glass, I constructed a pot furnace that allowed me to melt small batches of various colored glass formulas. At the time, I would casually throw in a teaspoon of this, a pinch of that and a dash of something else. After I had let the whole thing melt at a very high but random temperature, I would then make the resulting mixture into a platter or bowl or whatever, to see how it turned out. Basically, I was playing at glass chemistry. Most of the time, the result was interesting and I learned something from it, but only now and then was the artwork beautiful.

Then one time I made a mix that produced the most spectacular explosion of deep red-oranges and magentas swirling among jagged stripes of yellow-green and patches of brilliant blue. The colors were just so bright and beautiful…they took my breath away! (One of two platters I created from this melt is shown on page 95 of my book, the other is in the permanent collection of the Fuller Museum.)

Unfortunately, and typical of my offhand attitude at the time, I hadn't written down a speck of the formula! So I couldn't make it again - ever.

In the following months and years, I paid a terrible price for my unscientific approach: I tried to make that miraculous glass again and again for nearly a decade, but the results never came close to being good enough. It had worked once – why couldn't I make it again? The search just haunted me, and I vowed that one way or the other, someday, no matter what, I was going to figure this out.

Then in 1982 I was awarded a small grant from the Massachusetts Council on the Arts and Humanities. Because I’d been experimenting with silver at the time of my mysterious melt, I took all the grant money and bought several pounds of pure silver metal, which I self assuredly converted (don’t ask! This involves boiling nitric acid and billowing clouds of fumes) into silver nitrate. And then, every single week for an entire year, I melted that silver nitrate into different glass formulas. I also started keeping track of the minutia of each new melt, trying to be as scientific as possible.

One year went by, and I hadn’t figured it out. Then another year, and another. The results were variously striking, intriguing, boring, and sometimes dull as mud. And then I used up all the silver. It was so frustrating! I had to make a living. I had to focus on creating the work that galleries were selling. I didn’t have the money to buy more silver, nor the time to continue melting experimental glass every week.

Still haunted, I decided to make just one silver melt a year. And so I did, all through the 1980’s, ‘90’s, and early 2000’s, with varying levels of incremental success and understanding – but still no joy.

Then blind random luck! The investment firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, and along with collateralize debt obligations came the recession of 2008. Demand for my art vanished overnight and suddenly the time pressure to constantly make new artwork miraculously went away. At that point I could have chosen to stop working altogether, but I realized I was being handed an opportunity to return to my quest.

I have now made glass from more than 400 separate experiments. I’ve learned more and more about what I need to do, and, through an uncharacteristically meticulous process, discovered that success depends on factors far beyond the simple ingredients and the temperature of the furnace.

The result of this work is what I call Corona Glass. As a material, it remains quirky, unpredictable and endlessly fascinating to me, but at last I have finally started to make Corona platters, bowls and vases that are, increasingly reliably, truly beautiful.